The Health Of Old Colliers

By J. S. HALDANE, M.D., F.R.S., Director, Doncaster Coal-owners Research Laboratory.

Presented at the General Meeting of The Institution of Mining Engineers, 8 June 1916, London

Every ten years there is published an invaluable Supplement to the Registrar-General's Reports, in which the annual mortality in different occupations is set out and discussed generally, so that the relative healthiness of these occupations can be definitely gauged.

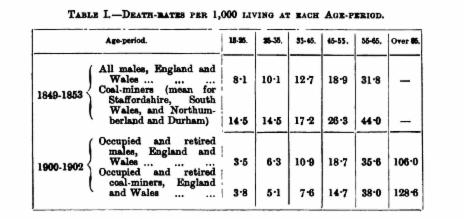

It was shown in the last Supplement, in connexion with the census of 1901, that the general death-rate among colliers was considerably lower than in the great majority of occupations. But there is an exception to this in the case of colliers above the age of 55. These points are shown in Table I., in which are also incorporated the earliest available official figures - those given in evidence before the Royal Commission on Mines that reported in 1864.

Table I - click on image to view full-size

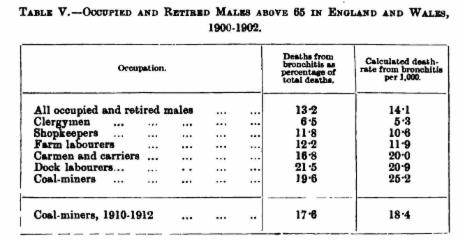

These figures are further analysed in Tables II., III., and IV.

Tables II, III and IV - click on image to view full-size

It will be seen from Table I. that whereas about 1851 the death-rates at all ages were considerably higher among colliers than among the general population, the converse was the case in 1901. About 1881 the rates had become about equal. In the fifty years from 1851 the death-rate fell greatly among the general population; but the fall is far more striking among colliers than in other occupations. Table II. shows the enormous fall in the accident death-rate among colliers. Table III. brings out the very significant fact that up to the age of about 50 the death-rate from lung diseases is much lower among colliers than in the average population, and was so even in 1851; whereas above 50 the converse is the case.

The purpose of this paper is, not to discuss the causes of the improvement, but to concentrate attention on the reason for the continued high death-rate among old colliers. According to the census of 1901, out of a total of 609,000 men employed as colliers, 35,800 (or 5.9 per cent.) were aged 55 to 65, and 10,000 (or 1.6 per cent.) above 65. It is thus only to a small proportion of actual colliers that the higher death-rate applies. Nevertheless, this higher death-rate must, if correct, be an index of much invalidity - of the premature wearing-out of many men. Hence the matter is one of serious concern.

As coal-mining is a strenuous occupation, it is natural that colliers should retire or go into some other occupation when they reach a certain age. From the census returns for 1901 it appears that for 1,000 men living at the age of 45 to 55 there were 650 at the age of 55 to 65, and 473 at over 65. Among colliers, on the other hand, for 1,000 employed at 45 to 55 there were only 479 returned as employed at 55 to 65, and 134 at over 65. If those returned as retired colliers be added, the numbers are still only 506 at 55 to 65, and 212 at over 65. It seems, therefore, that a large proportion of colliers do take to other occupations, or for some other reason were not returned as colliers.

Now the numbers of occupied and retired men in each occupation are taken from the census returns. On the other hand, the deaths, and the present or previous occupation to which each death is credited, are returned by the local registrars. If, therefore, the census and the registrars' returns are not both complete, the death-rates calculated from them will be more or less inaccurate. The last Decennial Supplement gives the death-rate for all males over 65 as 94.6 per 1,000, for all occupied males as 88.4, and for occupied and retired males as 106.2. From the figures given it follows that the calculated death-rate for retired males is 148.0. But the total of occupied and retired males above 65 is only 86 per cent, of all males above 65, and the missing 14 per cent, belong mainly, so far as can be judged, to the retired class. The "retired" and "missing" class together have a death-rate of 104.2, and this is probably about the real death-rate of the retired class. There can be no doubt that the returns of previous and present occupations of old persons by the registrars were much more complete than the census returns, so that the total of old persons to which the corresponding deaths were credited was too small, and the death-rate consequently too high.

This source of error appears to have told with special heaviness on the death-rates calculated for colliers above the age of 55, since so large a proportion of old colliers retire from their work as colliers, but may still come to be entered in either registrars' or census returns as either "occupied," or simply "unoccupied." In general the "retired" class in each occupation has a much higher calculated death-rate in each occupation than the "occupied" class. Most of the excess is only apparent, as just explained; but part is certainly real, and due to the facts that the "retired" class are older on an average, and that retirement has often been due to some ailment which ultimately proved fatal. In the case of colliers over 65, however, the calculated death-rate (109.6) is much lower among the "retired'' than among the "occupied" (139.8). The existence of this strange anomaly leaves little doubt as to the incorrectness of the death-rates for occupied and retired colliers as given in the last Decennial Supplement.

By the courtesy of the Registrar-General and of Dr. Stevenson, Superintendent of Statistics, the writer is enabled to refer to a few of the figures belonging to the next Decennial Supplement, which is delayed owing to the staff of the department being largely engaged in war work. These figures refer to the number and calculated death-rates of occupied and retired colliers over 65 in the years 1910-1912. It appears that in the census of 1911, 29,549 men were registered in the census as occupied and retired colliers, whereas only 15,879 were so registered in the 1901 census. It would be absurd to suppose that the number of old colliers had nearly doubled in ten years, so that the 1901 figures are clearly shown to have been wrong. The calculated death-rate among occupied and retired colliers in 1910-1912 was 105.5, instead of the high figure of 128.6 for 1900- 1902. The new figure is slightly lower than the corresponding one for all occupied and retired males in 1900-1902, and removes once for all the painful impression produced by the existing published figures.

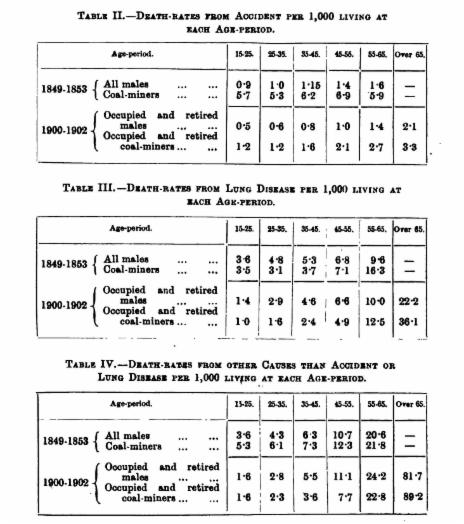

Whether, and if so to what extent, the true existing death-rate of occupied and retired colliers above the age of 55 is higher than in other occupations must remain in doubt for the present. The writer thinks, however, that it has been higher in the past; for, even if the older calculated death-rates are discarded, another method of judging is left. Different occupations leave their marks on men, and these marks are shown in tendencies to die more readily from certain affections. Now, if the proportions due to particular causes among the total deaths registered among occupied and retired colliers above the age of 55 be analysed, there appears to be a marked excess of deaths from bronchitis. This fact, as well as the great difference between different occupations with regard to the mortality from bronchitis in old age, is shown in Table V.

Table V - click on image to view full-size

This table indicates that there is a rough general relationship between mortality from bronchitis in old age and work involving considerable physical exertion. Many other occupations bearing out the same general conclusion might have been included.

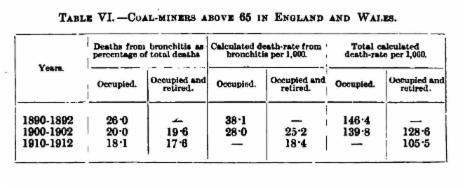

Let us now look at the bronchitis mortality among old colliers, as indicated by the figures of successive Decennial Supplements. Table VI. shows the figures since data on the subject were first published.

Table VI - click on image to view full-size

The table indicates very clearly that bronchitis has diminished greatly among old colliers since 1890, although it is still in excess.

The excessive bronchitis death-rate among colliers in 1890- 1892 was probably due to a considerable extent to the prevalence of dangerous influenza at that time, since the bronchitis death- rate was higher in all classes of the community than in 1900- 1902. But the relative excess among old colliers is none the less significant.

Table V. points, as already remarked, to a connexion between excessive physical exertion and a tendency to die of bronchitis in, old age. Now hard physical exertion is accompanied by hard breathing. The body does not wear out like a machine, since its substance is constantly being renewed; indeed, the maintenance of each organ is improved by due use. But over-use does produce injuries, and constant over-distension of the lungs tends to bring about what is known as " emphysema" - a condition, in which the delicate walls of the air-cavities of the lungs are more or less ruptured. With emphysema existing bronchitis becomes more dangerous; and it would seem that the increased tendency to death from bronchitis in occupations involving excessive exertion is due to the emphysema induced by over-stretching of the lungs during that exertion.

But why has bronchitis in old age diminished so greatly among coal-miners? Improvement in ventilation seems the most probable cause. So far as the writer can judge from enquiries, it was common 40 or 50 years ago for coal-miners to be working in air containing so much blackdamp that lamps or candles burned dimly. In such air there is usually 2 or 3 per cent, of carbon dioxide, which has an enormous effect in increasing the breathing during muscular exertion. The breathing is exactly regulated so as to keep an average of about 5.6 per cent, of carbon dioxide in the air filling the air-cavities of the lungs; and with 3 per cent, of this gas in the air a man breathes twice as much air, so as to keep the percentage right in the lungs. A man doing moderate muscular work in pure air would breathe about five or six times as much air as during rest. In air containing 3 per cent, of carbon dioxide he would be breathing ten or twelve times as much air as during rest, and his breathing would be taxed to the utmost. He would thus be much more liable to contract emphysema.

The better ventilation of coal-mines is largely a consequence of the greater amount of firedamp and greater heat met with as mines have become deeper, and the writer is inclined to think that both the firedamp and the heat have hitherto resulted indirectly in great improvement to the health of miners. Where there is plenty of firedamp there is usually also plenty of fresh and dry air, and no harmful excess of carbon dioxide. The proportion of deaths from bronchitis among old miners was higher in Staffordshire in 1890-1892 and 1900-1902 than in any of the other coalfields; and Staffordshire mines are on the whole exceptionally subject to blackdamp.

The excess in bronchitis among old coal-miners has been attributed to the breathing of dust, and the writer was previously inclined to agree with this theory. But it is very difficult to see why, if dust is the cause, there has been so great a diminution in the bronchitis mortality in recent years. Coalmines have, on the whole, become drier and more dusty with increasing depth and better ventilation; and, if dust were the cause, one would have expected the bronchitis to increase, whereas it has greatly diminished.

It is certainly the case that an excess in mortality from bronchitis is associated with the breathing of harmful dust. But this excess is accompanied by a far greater excess in mortality from phthisis, and begins comparatively early in life, unlike the bronchitis mortality of colliers.

The experiments carried out by Prof. J. M. Seattle on animals for the Eskmeals Committee .showed that both coal-dust and the shale-dust usually associated with it on mine roads are relatively harmless. Further experiments on the same subject have been carried out more recently by Dr. A. Mavrogordato in the writer's laboratory for the Medical Research Committee under the Insurance Act, and attention has been concentrated on the process by which dust is eliminated from the lungs. These experiments show that both coal-dust and shale-dust are readily eliminated by the agency of living cells, which collect the dust and then wander out with it into the bronchial tubes, whence it is swept upwards by the action of the ciliated epithelium which lines the air-passages. This ready elimination does not occur with other dusts known by human experience to be dangerous and liable, in particular, to predispose the persons concerned to phthisis.

To put the matter into metaphorical language, coal-dust and shale-dust, when introduced into the lungs, summon up the activities of thousands of tiny housemaids, who collect and gradually make away with the dust. If the quantity of dust inhaled is not too great, therefore, the cleaning-up process keeps pace with the introduction of the dust, and no harm results.

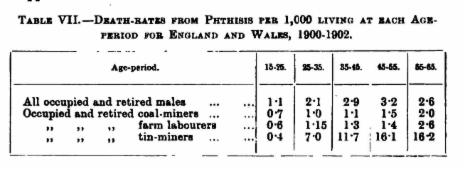

It is well known that colliers suffer very little from phthisis. The facts are so striking that the writer has embodied them in Table VII., which is constructed from data in the last Decennial Supplement.

Table VII - click on image to view full-size

This table shows that the phthisis death-rate among colliers is not only much lower than in nearly all other occupations, but is even lower than in the exceptionally healthy occupation of farm labourer, despite the advantages of pure air and relative segregation in the latter occupation. The low death-rate from lung disease among colliers up to the age of 55 is almost entirely due to their relative immunity from phthisis, and Table III. indicates that this immunity existed in 1850 just as now. Above the age of 55 their increased bronchitis death-rate in old age begins to tell heavily, and their general death-rate probably goes up correspondingly. For contrast, the figures for tin-miners, who are exposed to dangerous dust, are added in the table.

Coal-dust certainly does not kill germs; but it has come to be regarded by medical men as a preventive of phthisis. It seems probable, therefore, that the "housemaid" cells which clear out the dust-particles clear out at the same time other "foreign bodies," such as tubercle bacilli. If this is so, coal-dust in moderation is, on the whole, and despite explosions, an advantage to the safety of colliers. Town-dwellers and smokers may also take comfort to themselves in the thought that, in introducing smoke-particles into their lungs, they are educating their lung epithelium to deal with really harmful "foreign bodies." In any case the evidence does not now bear out the theory that the excessive bronchitis of old colliers is due to dust-inhalation.

The writer does not think that there is any evidence in favour of the idea that the excessive bronchitis in old colliers is due to exposure to changes of temperature. Miners do not appear to take harm in this way, so far as the writer has been able to ascertain; and in other occupations associated with exposure to extremes of weather, there is no excess of bronchitis among either young or old.

The practical conclusions to be drawn from this paper are: (1) that good ventilation is of considerable importance to the health and continued working efficiency of miners, as well as to their safety from accidents; and (2) that there is no real statistical evidence of harm resulting from the inhalation of coal-dust or shale-dust in the quantities ordinarily breathed by miners, and a strong presumption that the dust they breathe protects them against serious dangers.

It is satisfactory to find that the excessive death-rate among old colliers is to a large extent only apparent, and that the real excess of bronchitis from which they have suffered has greatly diminished.

Prof. Henry Louis (Armstrong College, Newcastle-upon- Tyne) suggested that it would add to the interest of the paper if tables were added giving the rates of wages paid to colliers during the periods dealt with. He thought that it would be found that wages played an exceedingly important part in the subject under discussion: first, because an increase in the rates of wages enabled a man to live much better from childhood upwards, and, secondly, because his better nourished body put him in a position to ward off disease. The wages earned at present by the collier allowed him to retire at a comparatively early age, and thus, being a man who had done a shorter spell of work in the pits and who was living a comfortable life in his retirement, he would be more immune from diseases than if he had had to continue work for a much longer period. It was very satisfactory to the coal-mining industry to learn from the paper that the efforts that had been made to improve the ventilation, etc., had been of direct benefit, to the health of the men employed in the mines.

Mr. D. M. Mowat (Coatbridge) said that Dr. Haldane had pointed out the great handicap under which a man working in bad air suffered, and the danger that he ran when working hard compared with a man who was quietly sitting still. It never paid to work a man in bad air, and nobody did it if he could avoid it, because, apart from the danger to the man himself, there was the question of expense. A man working in bad air could not do the amount of work that he otherwise would, and he would want to be paid a higher rate for so doing.

Mr. Arnold Lupton (London) said that he had long been of opinion that, in considering the safety of mines, it was necessary to take into account the sanitary conditions as well as the accident factors. Too much thought had been given in the past to the question of how to avoid accidents, without taking into consideration whether the methods adopted would introduce injuries to health that might cause far more deaths, disease, and misery than the occasional accidents which were so much deplored when they did arise. He would like to call attention to the danger from flint and granite dust, which was so harmful in the case of the Cornish tin-miners. What was the effect of the dust thrown up from the granite roads and other hard roads on people who lived beside them, or travelled on them, as compared with those who lived, say, near asphalted or wood-paved roads? Had asphalte or wood any special dangers of their own? It was mentioned in the paper that the grains of coal-dust or shale breathed by the colliers might help to carry out of the system the tubercle bacilli. Would the author pursue his investigations a little further, because he (Mr. Lupton) was of opinion that this belief in the tubercle bacillus as a cause of consumption was one which in a very short time the progress of science would prove to be erroneous. When the bacillus was found, it was a consequence, and not a cause.

Mr. T. H. Bailey (Birmingham) asked whether the effect of ventilation in workmen's houses in improving the health of colliers was not as important as the factors mentioned by Dr. Haldane in his paper. He had made enquiries in one of the working-class parishes of Birmingham, and found that during the past 20 years the health of the residents had vastly improved, as they were getting more into the habit of keeping their windows open both day and night. He was of opinion, therefore, that the ventilation of houses was quite as important as the ventilation of the places in which they worked.

Lieut.-Colonel W. C. Blackett (Sacriston) said that he was somewhat puzzled by the statistics put forward by Dr. Haldane. He did not know why the conclusion was arrived at that the highest death-rate of the older men was "an index of much invalidity - of the premature wearing-out of many men." If lives of various ages were saved during the earlier periods, and the men thus prevented from dying prematurely, a time would come at a later stage when they must die. This, however, did not prove that there was any alarming death-rate among the older men, as it was a natural consequence of the men having been prevented from dying earlier. If it were possible to keep such men alive until they were, say, 100 years old, and they all died at that age, it would be very easy to comment upon the extraordinary death-rate of men of 100 years as against a previous period when no one had ever died at that age. He was, therefore, by no means convinced that the statistics in the paper proved exactly what Dr. Haldane contended. The author had also stated that the prevalence of bronchitis was, as a rule, due to men working very hard, and later on he had answered the question why bronchitis in old age diminished so greatly among coal- miners by stating that it was owing to the improvements in the ventilation. It was rather illogical to state first that this bronchitis was mostly due to men working strenuously, and then to account for it by a totally different reason. It might be equally due, as Prof. Louis had hinted, to the fact that the men who formerly worked very hard did not do quite so much work now. This was quite a reasonable supposition, because men nowadays did not work quite so hard as they did in the olden times, when they worked much longer hours.

He would like to ask whether ordinary breathing, even if rapid, by expansion of the chest under atmospheric pressure, could damage the lung cell and cause emphysema as much as could forcible distension of the cell by contraction of the chest. He would like to hear more about other occupations in this connexion - say, the glass-blower, who did forcibly distend his lungs. Would he not much more readily suffer than the men who simply extended their lungs by allowing the air to enter at ordinary atmospheric pressure?

Dr. J. S. Haldane (Oxford), in reply, said that the glass- blowers' occupation did give rise to emphysema, and the same remark applied to people who played wind instruments, although there were exceptions in every case.

With regard to the question of hard work, if a man did not work so hard now, it might account for there being less emphysema; but his impression, after seeing colliers at work, was that it was not the number of hours that they worked, but the amount of labour that they put into their work. There appeared to be a very big strain on their lungs when they were not breathing perfectly pure air, but it was quite possible that colliers had not worked so hard during the last 20 years as in previous years. With regard to the invalidity question, he was afraid that he. had not made himself quite clear. All he meant to infer was that there might be extra invalidity because the colliers were more liable to bronchitis. If they got emphysema, it would be at a time when they ought to be working in good health, instead of which they were wheezing and unable to do any considerable work or make a livelihood. He did not think that people were on the whole less healthy for not having been killed off in their youth.

Lieut.-Colonel Blackett said that the figures set forth in the paper showed, however, that such was the case. If Dr. Haldane would examine Table III. ("Death-rates from Lung Disease"), he would see that at the first, second, third, and fourth age-periods there were fewer deaths from this cause than was the case amongst other classes. It was not until the fifth and sixth stages were reached that the deaths were more, and that, he maintained, was because "creaking hinges" had at last given way. That was, he contended, the logical conclusion to be drawn from the table.

Dr. Haldane said that, if Colonel Blackett would examine the figures again, he would find that what really had happened was that the men died less from phthisis at any age up to extreme old age, but that apparently at the age of 50 they began to die of bronchitis in a way that no other people did. It was not because there were more of them: for it was the rate per thousand living at that particular age that he had dealt with.

With regard to Mr. Bailey's remarks as to the benefit arising from open windows, he quite agreed with him on that point; but the liability to bronchitis was a special factor which he did not think had anything to do directly with open windows. They probably helped considerably in the diminution in the death-rate in the general population, and the death-rate, of course, had diminished, but he was not sure that this factor applied much to those working underground.

Mr. Lupton had raised a very interesting question about the breathing of dust from roads, and asked whether it did harm. It was quite possible, however, that the amount of horse manure lying on the road might act as a preventive and save us from miners' phthisis. He did not actually mean to suggest that this was the case, but its presence was one of those little things that made all the difference. The question whether one dust was not an antidote for another was now being worked out - whether, for instance, a dust which by itself would be dangerous would be rendered innocuous in the presence of coal-dust. Thus the introduction of coal-dust into the Transvaal mines might result in clearing out from the cells of the lungs the whole of the dangerous silica dust as well as other harmful matter. These were all very interesting questions, but at present there were no proper data available respecting them. There were, however, data with regard to shale-dust, and there was no doubt that it contained quartz. Dr. A. Mavrogordato was now working at this question. The quartz seemed to be all cleared out of the lungs when shale-dust was given to animals, whereas pure quartz was not. He would have been inclined to agree with Prof. Louis's suggestion respecting the effect of high wages, except for the fact that, taking the case of farm labourers, whose wages were extremely low as compared with other classes, it was found that they had the least general mortality. They did not stand quite so well in phthisis, but in other complaints their status was better, although their wages were extremely low when compared with those of colliers. It was, of course, essential that a man and his family should have enough food to enable him to lead a healthy life, but he was not sure that the wages question had very much to do with the death-rate of colliers. That, however, was a matter of opinion.

Mr. John Gerhard (Worsley) called attention to the fact that the statistics in the paper took them down to the year 1902. The Eight Hours' Act came into force in 1909, and was followed by the Minimum Wage Act, the abnormal places rates, and war bonuses, all of which meant considerable advances in wages. The effect of these enactments would be shown in subsequent tables.

Dr. Edgar L. Collis (Medical Inspector of Factories, Home Office) wrote that the exact causation of the high respiratory mortality at late ages could not be ascertained until the various groups clashed as miners were subdivided : thus the working conditions of (1) coal-getters, (2) road-makers underground, and (3) other men engaged about a coal-mine, varied considerably. Bronchitis, however, which was chiefly considered, was a condition causing much pre-mortem invalidity: a study of such invalidity among the various groups indicated would probably afford useful and sufficient data. The varying mortality from this disease among miners in different coalfields was of great interest, and worthy of close study.

Mi'. Charles Carlow (Leven, Fife) wrote that one of the miners at the collieries belonging to the Fife Coal Company, Limited, had recently retired from active underground work at the age of 82. This man had commenced work at the age of 10 at Kelty Colliery, and had worked in the same mine for 71 years, with the exception of three weeks. He (Mr. Carlow) had taken over the management of that colliery 43 years ago, and in 1914 had at his table thirty-five workmen (from 65 to 80 years of age) who had never left the colliery during that period. They had all been hard-working loyal fellows, and were in very good health for their years. Some of them had retired, but most of them were still working. The output of Kelty Colliery in 1873, when these thirty-five old men were at work there, was only 300 tons per day, so that they represented a considerable proportion of the total men employed.

Mr. W. N. Wilson, Junr. (Chopwell) wrote that his experience was that bronchial and asthmatical colliers were particularly sensitive to the fumes produced by explosives, even under conditions which caused absolutely no inconvenience to colliers in normal health. This inconvenience might be only temporary, but he was inclined to think that it was serious, and that possibly the previous use of explosives in moderately ventilated mines was in some degree the original cause of bronchitis among the aged colliers of today. If this opinion were correct, the present higher standard of ventilation might produce a greater improvement in the mortality from bronchitis among aged colliers than was anticipated by Dr. Haldane. Tables comparing the mortality from bronchitis among aged coal-miners and aged metal- miners would have been instructive. Generally speaking, metal- miners use more explosives than coal-miners. The dust produced was injurious, and the men had frequently to perform the very laborious work of climbing long vertical ladders. The use of vertical ladders was now not as frequent as was the case a few years ago, and Dr. Haldane would probably be in a position to state how the percentage of blackdamp in metal-mines compared with the percentage met with in coal-mines.

Dr. Haldane wrote that, while he agreed with Dr. Collis, he feared that it would not be possible in practice to classify coal- miners according to the nature of their work, as they went from one class of employment to others.

What Mr. Wilson had stated about the effects of fumes from explosives would certainly help to explain the fall in the bronchitis death-rate among old colliers. In his (Dr. Haldane's) experience there was less blackdamp in the air of metal-mines (where the dust was dangerous) than in most coal-mines.