Housing of Scottish Miners – Report on the Housing of Miners of Stirlingshire and Dunbartonshire

By John C. M'Vail, M.D., LL.D. County Medical Officer - Part 2

Part III - HOUSES BUILT BEFORE 1899.

In the landward districts of the Counties of Stirling and Dunbarton the number of houses erected previous to the passing of the Building Bye-laws in 1899 and occupied by miners at the time of the police census in June 1909, was 1,881. This is more than double the number of the houses built since 1899. As will be seen later on, very many of the older houses have been repaired or renovated within the last few years. Their age varies greatly. The most ancient of all are in the neighbourhood of Carron, and belong to or have been leased by Carron Company. One three-storey tenement of eight dwellings dates back to 1770. Other three houses were built in 1803. A small village which has just been closed against human habitation belongs to 1804, and another row which is still occupied dates from 1806. Next to these in age come various rows in the southern part of East Stirlingshire - Redding, Reddingmuirhead, Wallacestone, Canal Row, Middlerigg, Wester Shieldhill, Summerhouse, and Rumford Square. They were erected between the years 1829 and 1839 and still give accommodation to a very considerable population. The village of California, also in South East Stirlingshire, was built in 1849, and no doubt took its name from the region of the gold boom at that time, just as a modern colliery in the same part of the county was christened Klondyke by the miners - and I have heard two or three houses attached to it go by the name of Dawson City. Blackbraes, near California, belongs to the same period, and so also do the rows at Skinflats in the Bothkennar part of Grangemouth parish. The village of Knightswood in East Dunbartonshire is nearly as old. Between 1860 and 1875 a large number of miners' houses were built. These include the principal colliery villages in East Dunbartonshire – Smithston, Overcroy, Twechar, part of Barrhill, Auchinstarry, and Langmuir Rows. Langdyke and Glen Village in Eastern Stirlingshire and the older rows at East Plean in Central Stirlingshire belong to the same period. The houses at Wester Gartshore in Eastern Dunbartonshire were erected in 1880. Since the passing of the Local Government Act of 1889, under which County Councils were created, but previous to the Building Bye-laws, which came into force ten years later, a number of houses, including the village of Queenzieburn, in Kilsyth parish, the greater part of Standburn, in Muiravonside, and some at Banknock, were built, and the officers of the District Committee were consulted with regard to the plans of certain of them. The earlier rows of some of the modern villages in Central Stirlingshire belong to the same period.

Structure.- The walls, of stone or brick, are never hollow in the older houses, and are very seldom strapped and lathed under the plaster. Damp-proof courses at the base are absent. The floors may be of wood, or pavement brick, or stone flags, or lime cement. The room may have a wood floor, and the kitchen a brick or stone or lime floor. The floors are usually at or near the ground level, and the wood floors were seldom or never ventilated underneath when the houses were built. Also, rain gutters may not have been provided, or may have become broken or useless in course of time, and may not have been renewed. Commonly such rain gutters as exist were designed to discharge into water barrels, but sometimes these have been wanting, with the rain discharging at the base of the walls.

The ground level outside the back or gables of the houses may be higher than the floor level, and surface water may drain towards the house walls. Under such conditions damp has been a most common defect in these old houses.

All the houses now in question having been built prior to 1899, it is impossible to give with the same approach to accuracy statistical information such as has been furnished by plans lodged , under the Building Bye-laws. But for purposes of comparison some figures are submitted regarding 1,643 of the 1,881 houses built before 1899. It is to be clearly understood that the figures are no more than approximately correct.

Dimensions. Number of Apartments.- Of the 1,643 houses 424, or 25.80 per cent., are of one apartment; 1,175, or 71.51 per cent., are of two apartments ; 32, or 1.95 per cent., are of three apartments; 11, or 0.67 per cent., have four apartments; and 1, or 0.06 per cent., has more than four apartments (This is a manager's house).

Cubic Capacity.- The cubic space is less than in modern houses. The ceilings are lower, and the apartments smaller. Not infrequently the houses are only one room deep, and two or occasionally three adjoining apartments, each originally a one roomed house, are taken by one family and used as a single dwelling.

Bedplaces.- Structurally these are nearly always open entirely from floor to ceiling and from side to side, but, as already noted, ventilation is much interfered with by the housewife's curtains hung at the top and sides.

Sculleries.- These seldom exist in old houses. Sometimes there is an entrance porch which serves as a store, and partly also as a scullery, but without a water tap or sink.

Light and Ventilation.- There is always a front window adjoining the door. Usually it is not very large, and its top is not infrequently too far from the ceiling. Where the walls are low cubic space may have been gained by 'camceiling,' and this space is never properly ventilated. The front windows are mostly sashed, but are not usually hung on cords with pulleys for proper opening. Confining the figures to the 1,175 houses of two apartments, about 432, or 36.8 per cent., have their sashed windows double hung. Commonly the lower sash can be raised and kept open on a support of some sort, but the upper part opens only for a few inches, and that not conveniently, perhaps only from the outside. Occasionally there is only a single hinged pane in the corner of the window. A small hinged window in the back wall of houses which are only one room deep greatly aids ventilation.

Inside Water Supply.- Of the 1,643 houses the total number with water, supply indoors is only about 45. The occupiers of all the rest go outside for their water, usually to pillar wells at the further side of the pathway in front.

Baths.-None of the 1,643 houses have baths.

Washing Houses.- Of the 1,643 houses only about 400, or 24.3 percent, are provided with washing houses. All the rest, or 75.7 percent, have to do their domestic washing in a tub placed on a chair or trestle, either within the kitchen or outside if the weather permit.

Coal Storage.- Of the 1,643 houses about 470, or 28.6 percent, are entirely without coal houses; and to this number may properly be added about 120, or 7.3 percent, in a village where the coal houses are in such a ruinous condition as to be unusable. It may be taken that in nearly all these 590 houses coals are stored underneath a kitchen bed.

Sanitary Conveniences.- Of the 1,643 houses 119, or 7.2 percent, have the use of water closets. The rest depend on outside dry closets or privies, excepting a few which have been without any such accommodation.

Refuse is deposited in ashpits, most of which are roofed. In South Eastern Stirlingshire, where the villages are nearly all old, of 555 houses regarding which note was taken, 383 have the use of roofed ashpits and 172 of open ashpits.

Drainage.- The drainage is not nearly so good as in the newer houses. There are few underground drains. Some of the open channels are badly laid with insufficient gradient and irregular surface. In very few villages are the channels flushed automatically, but where such flushing exists it is very valuable.

Roadways and Footpaths.- The conditions are very different in different villages. In a few cases they are very bad, the surface of the private roads being very irregular, with deep ruts and pools of mud in bad weather. Access in one or two instances is even dangerous, especially at night. But in the great majority the roads are in very fair order.

Structure.- The walls, of stone or brick, are never hollow in the older houses, and are very seldom strapped and lathed under the plaster. Damp-proof courses at the base are absent. The floors may be of wood, or pavement brick, or stone flags, or lime cement. The room may have a wood floor, and the kitchen a brick or stone or lime floor. The floors are usually at or near the ground level, and the wood floors were seldom or never ventilated underneath when the houses were built. Also, rain gutters may not have been provided, or may have become broken or useless in course of time, and may not have been renewed. Commonly such rain gutters as exist were designed to discharge into water barrels, but sometimes these have been wanting, with the rain discharging at the base of the walls.

The ground level outside the back or gables of the houses may be higher than the floor level, and surface water may drain towards the house walls. Under such conditions damp has been a most common defect in these old houses.

All the houses now in question having been built prior to 1899, it is impossible to give with the same approach to accuracy statistical information such as has been furnished by plans lodged , under the Building Bye-laws. But for purposes of comparison some figures are submitted regarding 1,643 of the 1,881 houses built before 1899. It is to be clearly understood that the figures are no more than approximately correct.

Dimensions. Number of Apartments.- Of the 1,643 houses 424, or 25.80 per cent., are of one apartment; 1,175, or 71.51 per cent., are of two apartments ; 32, or 1.95 per cent., are of three apartments; 11, or 0.67 per cent., have four apartments; and 1, or 0.06 per cent., has more than four apartments (This is a manager's house).

Cubic Capacity.- The cubic space is less than in modern houses. The ceilings are lower, and the apartments smaller. Not infrequently the houses are only one room deep, and two or occasionally three adjoining apartments, each originally a one roomed house, are taken by one family and used as a single dwelling.

Bedplaces.- Structurally these are nearly always open entirely from floor to ceiling and from side to side, but, as already noted, ventilation is much interfered with by the housewife's curtains hung at the top and sides.

Sculleries.- These seldom exist in old houses. Sometimes there is an entrance porch which serves as a store, and partly also as a scullery, but without a water tap or sink.

Light and Ventilation.- There is always a front window adjoining the door. Usually it is not very large, and its top is not infrequently too far from the ceiling. Where the walls are low cubic space may have been gained by 'camceiling,' and this space is never properly ventilated. The front windows are mostly sashed, but are not usually hung on cords with pulleys for proper opening. Confining the figures to the 1,175 houses of two apartments, about 432, or 36.8 per cent., have their sashed windows double hung. Commonly the lower sash can be raised and kept open on a support of some sort, but the upper part opens only for a few inches, and that not conveniently, perhaps only from the outside. Occasionally there is only a single hinged pane in the corner of the window. A small hinged window in the back wall of houses which are only one room deep greatly aids ventilation.

Inside Water Supply.- Of the 1,643 houses the total number with water, supply indoors is only about 45. The occupiers of all the rest go outside for their water, usually to pillar wells at the further side of the pathway in front.

Baths.-None of the 1,643 houses have baths.

Washing Houses.- Of the 1,643 houses only about 400, or 24.3 percent, are provided with washing houses. All the rest, or 75.7 percent, have to do their domestic washing in a tub placed on a chair or trestle, either within the kitchen or outside if the weather permit.

Coal Storage.- Of the 1,643 houses about 470, or 28.6 percent, are entirely without coal houses; and to this number may properly be added about 120, or 7.3 percent, in a village where the coal houses are in such a ruinous condition as to be unusable. It may be taken that in nearly all these 590 houses coals are stored underneath a kitchen bed.

Sanitary Conveniences.- Of the 1,643 houses 119, or 7.2 percent, have the use of water closets. The rest depend on outside dry closets or privies, excepting a few which have been without any such accommodation.

Refuse is deposited in ashpits, most of which are roofed. In South Eastern Stirlingshire, where the villages are nearly all old, of 555 houses regarding which note was taken, 383 have the use of roofed ashpits and 172 of open ashpits.

Drainage.- The drainage is not nearly so good as in the newer houses. There are few underground drains. Some of the open channels are badly laid with insufficient gradient and irregular surface. In very few villages are the channels flushed automatically, but where such flushing exists it is very valuable.

Roadways and Footpaths.- The conditions are very different in different villages. In a few cases they are very bad, the surface of the private roads being very irregular, with deep ruts and pools of mud in bad weather. Access in one or two instances is even dangerous, especially at night. But in the great majority the roads are in very fair order.

PART IV.

ADMINISTRATION.

The previous parts of this report have been confined to a statement of facts. It is proposed now to consider the facts in their bearing on the general administration of the villages. In doing so I begin with what is at the present time by far their commonest and most serious defect.

(1) REFUSE REMOVAL.

The most flagrant nuisance that can be found in a village community, whether mining or ordinary, is the privy-midden or privy-ashpit system, which still prevails in so many places in Scotland. It exists, though in very differing degrees, at most of the colliery rows in these counties.

Nothing puzzles me more in rural public health administration than the common failure to realise the importance of very frequent removal of filth from the immediate neighbourhood of groups of dwellings. Other things being equal, the larger the population and the longer the intervals between removal the worse is the nuisance. There can be no greater contrast between the amenity and health conditions of two otherwise similar communities than that which results from daily clearance of refuse, as contrasted with the accumulation for a month or more of the whole festering filth of the place, in privies and ashpits dotted throughout a village. Such privy middens, situated perhaps only ten or fifteen yards, occasionally much less, from dwelling-house doors and windows are a source of constant complaint by the inhabitants, especially in summer. They are serious factors in the production and conveyance of disease, particularly by the breeding of flies, which, with their feet dipped in filth, invade the houses and settle on articles of diet, including milk and jam and butter, and on children's faces after food. Also, dogs and cats may rake amongst,the refuse and afterwards play with the children, or contaminate food or milk, often standing exposed on a kitchen table.

The emptying of such privy ashpits is a particularly loathsome process and spectacle. The illustration (Fig. 15) shows an ashpit in course of being emptied, and only about 15 feet from the windows of a colliery row.

Fig 15.

In Special Scavenging Districts, formed under the Local Government and Public Health Acts, and administered by the sanitary authorities, the aim usually is and always should be frequent refuse removal. Not uncommonly in such special districts, even under the strict rating limits of the Local Government (Scotland) Act, 1894, a daily service has been possible, and now that the Act of 1908 is in operation this should become the general rule. Colliery villages are seldom within special scavenging districts, but there is no good reason why they should not be as well kept in this respect by the owners as is the best managed special district by the Local Authority. Even in the absence of water closets, daily or very frequent refuse removal is quite practicable by means of pail privies and movable dustbins, both being emptied into the scavenger's cart. If the work is not undertaken by the owners, then the village, if large enough, should be formed into a special scavenging district, and to facilitate that being done, a requisition under Section 44 of the Act of 1894 should not be essential. Local Authorities should be endowed with the same power of proceeding on their own initiative with regard to scavenging districts as they are with regard to drainage and water supply districts under Sections 122 and 131 of the Public Health (Scotland) Act, 1897. Where a village is inconveniently small for this purpose, the mine owners have the great advantage that, the whole place being theirs, they can make much better arrangements than in an ordinary hamlet ' where every house has a separate owner. The question is simply one of expense, and the profit far exceeds the outlay, as respects both health and decency. Of course those who receive the benefit should defray the cost. In special scavenging districts the rate is leviable one-half on owners and one-half on occupiers. That is quite equitable. The occupier is benefited in respect of the health and comfort of himself and his family ; the owner is saved the disorganisation of his work and the general ill effects which result from outbreaks of infectious disease, especially of enteric fever spread by means of filth accumulations.

Even at present, whenever enteric fever is known to exist at a colliery village the owners at once comply with my request to institute very frequent refuse removal and to continue it until the outbreak is at an end. There is no good reason why a course which can be adopted and continued for weeks or perhaps months whilst disease actually exists should not be a feature of village administration when outbreaks are absent. It is much better to prevent than to stamp out epidemics. If existing rents are too low, the occupier's share of the cost of more frequent scavenging would just have to be added.

In the case of rows attached to dying collieries, where it is desired by the owners that structural alterations be minimised, cleanly conveniences and daily refuse removal would do more to excuse continued occupancy than any other single item in the code of sanitation.

It is a pleasure to be able to state that in one of the largest mining villages of the two counties daily refuse removal is a feature of the owners' management. In another village which has had a very unfortunate experience of enteric fever, daily removal has been instituted. In some others the regularity and thoroughness of cleansing of privy ashpits have been much improved. But there can be regularity without frequency, and systematic monthly emptying is utterly insufficient.

In a few old rows in South East Stirlingshire, sanitary conveniences were entirely wanting until recently. Under such circumstances, fields and woods and hedgerows were resorted to, and domestic refuse was dumped anywhere in the neighbourhood of the rows. While this was quite opposed to the habits of a well-governed community and was an abominable training for children, yet the resulting nuisance was really less than under the conditions above discussed, where filth is accumulated in large quantities in the midst of villages, without frequent removal.

In reply to my expostulations on this subject a former mine owner once told me about his earliest efforts to provide sanitary conveniences for places where such primitive habits prevailed. He said that outhouses of brick or stone had been tried, but were quickly destroyed: Then cast-iron erections, such as are provided in towns for public use, were purchased, but even these could not resist the attacks made on them, and only the framework, being the stronger part, was left standing. Such a skeleton, with the sun and sky showing through it, made a very peculiar object on a moorland behind an old colliery row. Next, and finally, sheet iron was used for privies, and a ring section of an old pit-head engine boiler was placed behind it for an ashpit. Some of these still remain, and though rust has partly destroyed the sheet iron, the boiler sections have withstood the ravages both of man and of nature.

A Vicious Circle.- The mine owner is apt to attribute the destructive practices which occasionally lay waste the outhouses of a row solely to malicious mischief. But there are faults on both sides, and sometimes the greater blame lies at the door of the employer, or perhaps of his predecessors who first opened up the coal-field.

In districts where mining dates back to the earlier half of last century the houses were erected with little regard to or knowledge of the elements of sanitation. Some of these still stand and many others have stood until recently. Though many well-behaved and cleanly miners and their wives occupy and make the most of these old and defective dwellings and villages, yet it cannot be expected that the best class of employees will continue to live under inferior conditions if they can find better. They make their way elsewhere and their places are taken by a less desirable class, who may do much to nullify the efforts at improvement made by the mine owner, whether of his own accord or under pressure by the sanitary authority. And so a vicious circle is established : bad houses bring bad tenants, and bad tenants make repair of houses more or less futile. They break new lath and plaster, injure new kitchen ranges, entirely neglect cleanliness and ventilation, and annoy their neighbours by dirty habits both indoor and out. But if thorough instead of half-hearted renovation is the policy of the owners, if a capable caretaker is appointed, and outside cleansing systematically maintained, the bad tenants can be gradually cleared out and a better glass induced to take their place.

General Scavenging.- While the emptying of privy middens is occasionally left to a contractor, perhaps a neighbouring farmer, whose visits are far too infrequent, and whose work may be very perfunctorily performed, matters are very much better in respect of cleansing of surface channels and drains and roadways. I think there is no exception to the rule that mine owners employ a scavenger to give his whole time to these matters. The result of his labours depends a good deal on the structural conditions with which he has to deal. If the channels and roadways are well made, they are easily kept clean, but otherwise the reverse is the case.

The scavenger's duty usually includes attention to privy floors and seats. Where these dry closets are under lock and key, and each convenience duly allocated to certain households, little attention is required. Where, on the other hand, there are no locks and keys, and no allocation, the scavenger's toil is like that of Sisyphus. No sooner has he swept out a privy floor than its defilement by children is resumed, and such places are inevitably in a condition which makes them utterly unusable by any self-respecting adult. Here again the defence may be that allocation is a failure because keys get lost and locks broken and doors torn from their hinges. But that, is simply another phase of the vicious circle. If a village is badly planned so that the closets are inconveniently situated and without suitable access, and if in other respects the place is repellent to families who have seen better conditions elsewhere, then though it may have many cleanly inhabitants struggling to live a decent life in adverse circumstances, its population will yet include many whose dirty habits and destructive tendencies go far to counteract any but the most determined efforts at improvement. But the difficulties are by no means insuperable if the facts are fairly faced and grappled with.

Water Closets.- In the most modern villages or rows the , arrangements are usually very satisfactory. As shown in the plans on page 30, in one of the streets of houses at East Plean, known as South Plean Cottages, each dwelling has a good water closet opening off a scullery in an annex to the house.[Similar plans have been followed in a new row of houses at Rumford, belonging to Carron Company.] At Fallin (see page 31) there is a water closet to every pair of houses, so situated as to leave no doubt about responsibility for its being kept in order. In the photograph (Fig. 16) the middle door on the balcony, and the corresponding door on the lower flat is that of the water closet. When miners' rows are within a special water supply and drainage district, water closets are often introduced even for old houses. This is the case at Carron, Carronshore, and Carronhall, and has made a vast difference in the amenity of the rows.

Fig 16.

The introduction of water closets must usually be conditional on the practicability of purification of the sewage before discharge into a stream. In some cases tidal waters may be the natural point of effluence, and no treatment would be required. This is the case at Fallin. In the special drainage district which embraces the Carron rows the sewage is treated. East Plean, where some houses have water closets and others are in course of being provided, already constitutes a special drainage district, with septic tank and percolation and filter-beds. Independently of the existence of water closets, liquid refuse from village dwelling houses and washing houses is commonly itself discharged under conditions making purification necessary.

Where water closets are provided dry refuse is easily disposed of. By far the best system is its deposit in dust-bins or pails, and daily removal therefrom by cart. This practice is followed with the best results by the owners at Fallin, and by the Sanitary Authority at Carron Company's villages just named, which are within a special scavenging district. It is being arranged for also at East Plean.

Dry Closets.- Privacy and responsibility should always be aimed at in respect of privies as well as water closets. In the large modern village of Cowie, water closets have not yet been introduced owing to present impossibility of getting wayleave for a sewage drain, but it is expected that this will shortly be obtained. I mention Cowie because, even with its dry-closet system, privacy has been reasonably achieved by the closet being placed in an annex near the house door. The photograph (Fig. 17) fails to do justice to it because only one side of the semi-enclosure is included. The plan on page 27 shows the arrangement better. But a water closet is much better than a privy in such a situation.

Fig 17.

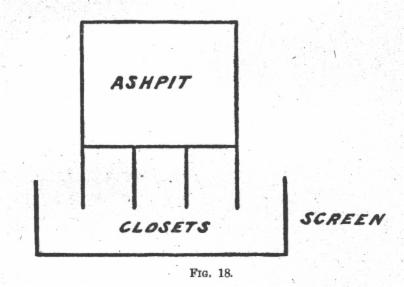

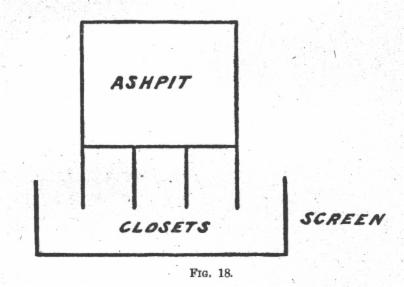

The Block System.- In the older, and in some modern collieries privacy and responsibility: are rendered very difficult by the block system of outhouses which is almost universal where dry closets are provided. The situation of these blocks, is shown in the diagram at pages 13 (Fig 1), 29 (Fig 11), and 32 (Fig 14), and is well indicated in the photograph (Fig. 2) opposite p. 14. As a rule the blocks contain wash-houses, coal-houses, privies, and ashpit. It is true that the closets are always on the further side from the dwellings, but there may be other dwellings beyond, and in any case they cannot be approached without a degree of publicity, which is very deterrent to women. In some rows, in despair of keeping doors in order, brickwork screens have been built instead.

Back Doors.- It may be pointed out here that in connection with the disposal of refuse the want of a back door to a house may be a very great inconvenience. In most mining villages the roadways are private, and the blocks of outbuildings are in front of the houses, so that access to them is from the front doors. But occasionally a miners' row faces a public road, and the outbuildings are at the back. If there are no back doors the occupiers have to carry their refuse along the front street, and then through a close or passage to the back. But the row may have no such passage, and buckets of refuse may have to be carried right to the end of the houses, and thence into the back yard. In such cases doors should be opened in the back walls to allow direct access to the premises in the rear.

The emptying of such privy ashpits is a particularly loathsome process and spectacle. The illustration (Fig. 15) shows an ashpit in course of being emptied, and only about 15 feet from the windows of a colliery row.

Fig 15.

In Special Scavenging Districts, formed under the Local Government and Public Health Acts, and administered by the sanitary authorities, the aim usually is and always should be frequent refuse removal. Not uncommonly in such special districts, even under the strict rating limits of the Local Government (Scotland) Act, 1894, a daily service has been possible, and now that the Act of 1908 is in operation this should become the general rule. Colliery villages are seldom within special scavenging districts, but there is no good reason why they should not be as well kept in this respect by the owners as is the best managed special district by the Local Authority. Even in the absence of water closets, daily or very frequent refuse removal is quite practicable by means of pail privies and movable dustbins, both being emptied into the scavenger's cart. If the work is not undertaken by the owners, then the village, if large enough, should be formed into a special scavenging district, and to facilitate that being done, a requisition under Section 44 of the Act of 1894 should not be essential. Local Authorities should be endowed with the same power of proceeding on their own initiative with regard to scavenging districts as they are with regard to drainage and water supply districts under Sections 122 and 131 of the Public Health (Scotland) Act, 1897. Where a village is inconveniently small for this purpose, the mine owners have the great advantage that, the whole place being theirs, they can make much better arrangements than in an ordinary hamlet ' where every house has a separate owner. The question is simply one of expense, and the profit far exceeds the outlay, as respects both health and decency. Of course those who receive the benefit should defray the cost. In special scavenging districts the rate is leviable one-half on owners and one-half on occupiers. That is quite equitable. The occupier is benefited in respect of the health and comfort of himself and his family ; the owner is saved the disorganisation of his work and the general ill effects which result from outbreaks of infectious disease, especially of enteric fever spread by means of filth accumulations.

Even at present, whenever enteric fever is known to exist at a colliery village the owners at once comply with my request to institute very frequent refuse removal and to continue it until the outbreak is at an end. There is no good reason why a course which can be adopted and continued for weeks or perhaps months whilst disease actually exists should not be a feature of village administration when outbreaks are absent. It is much better to prevent than to stamp out epidemics. If existing rents are too low, the occupier's share of the cost of more frequent scavenging would just have to be added.

In the case of rows attached to dying collieries, where it is desired by the owners that structural alterations be minimised, cleanly conveniences and daily refuse removal would do more to excuse continued occupancy than any other single item in the code of sanitation.

It is a pleasure to be able to state that in one of the largest mining villages of the two counties daily refuse removal is a feature of the owners' management. In another village which has had a very unfortunate experience of enteric fever, daily removal has been instituted. In some others the regularity and thoroughness of cleansing of privy ashpits have been much improved. But there can be regularity without frequency, and systematic monthly emptying is utterly insufficient.

In a few old rows in South East Stirlingshire, sanitary conveniences were entirely wanting until recently. Under such circumstances, fields and woods and hedgerows were resorted to, and domestic refuse was dumped anywhere in the neighbourhood of the rows. While this was quite opposed to the habits of a well-governed community and was an abominable training for children, yet the resulting nuisance was really less than under the conditions above discussed, where filth is accumulated in large quantities in the midst of villages, without frequent removal.

In reply to my expostulations on this subject a former mine owner once told me about his earliest efforts to provide sanitary conveniences for places where such primitive habits prevailed. He said that outhouses of brick or stone had been tried, but were quickly destroyed: Then cast-iron erections, such as are provided in towns for public use, were purchased, but even these could not resist the attacks made on them, and only the framework, being the stronger part, was left standing. Such a skeleton, with the sun and sky showing through it, made a very peculiar object on a moorland behind an old colliery row. Next, and finally, sheet iron was used for privies, and a ring section of an old pit-head engine boiler was placed behind it for an ashpit. Some of these still remain, and though rust has partly destroyed the sheet iron, the boiler sections have withstood the ravages both of man and of nature.

A Vicious Circle.- The mine owner is apt to attribute the destructive practices which occasionally lay waste the outhouses of a row solely to malicious mischief. But there are faults on both sides, and sometimes the greater blame lies at the door of the employer, or perhaps of his predecessors who first opened up the coal-field.

In districts where mining dates back to the earlier half of last century the houses were erected with little regard to or knowledge of the elements of sanitation. Some of these still stand and many others have stood until recently. Though many well-behaved and cleanly miners and their wives occupy and make the most of these old and defective dwellings and villages, yet it cannot be expected that the best class of employees will continue to live under inferior conditions if they can find better. They make their way elsewhere and their places are taken by a less desirable class, who may do much to nullify the efforts at improvement made by the mine owner, whether of his own accord or under pressure by the sanitary authority. And so a vicious circle is established : bad houses bring bad tenants, and bad tenants make repair of houses more or less futile. They break new lath and plaster, injure new kitchen ranges, entirely neglect cleanliness and ventilation, and annoy their neighbours by dirty habits both indoor and out. But if thorough instead of half-hearted renovation is the policy of the owners, if a capable caretaker is appointed, and outside cleansing systematically maintained, the bad tenants can be gradually cleared out and a better glass induced to take their place.

General Scavenging.- While the emptying of privy middens is occasionally left to a contractor, perhaps a neighbouring farmer, whose visits are far too infrequent, and whose work may be very perfunctorily performed, matters are very much better in respect of cleansing of surface channels and drains and roadways. I think there is no exception to the rule that mine owners employ a scavenger to give his whole time to these matters. The result of his labours depends a good deal on the structural conditions with which he has to deal. If the channels and roadways are well made, they are easily kept clean, but otherwise the reverse is the case.

The scavenger's duty usually includes attention to privy floors and seats. Where these dry closets are under lock and key, and each convenience duly allocated to certain households, little attention is required. Where, on the other hand, there are no locks and keys, and no allocation, the scavenger's toil is like that of Sisyphus. No sooner has he swept out a privy floor than its defilement by children is resumed, and such places are inevitably in a condition which makes them utterly unusable by any self-respecting adult. Here again the defence may be that allocation is a failure because keys get lost and locks broken and doors torn from their hinges. But that, is simply another phase of the vicious circle. If a village is badly planned so that the closets are inconveniently situated and without suitable access, and if in other respects the place is repellent to families who have seen better conditions elsewhere, then though it may have many cleanly inhabitants struggling to live a decent life in adverse circumstances, its population will yet include many whose dirty habits and destructive tendencies go far to counteract any but the most determined efforts at improvement. But the difficulties are by no means insuperable if the facts are fairly faced and grappled with.

Water Closets.- In the most modern villages or rows the , arrangements are usually very satisfactory. As shown in the plans on page 30, in one of the streets of houses at East Plean, known as South Plean Cottages, each dwelling has a good water closet opening off a scullery in an annex to the house.[Similar plans have been followed in a new row of houses at Rumford, belonging to Carron Company.] At Fallin (see page 31) there is a water closet to every pair of houses, so situated as to leave no doubt about responsibility for its being kept in order. In the photograph (Fig. 16) the middle door on the balcony, and the corresponding door on the lower flat is that of the water closet. When miners' rows are within a special water supply and drainage district, water closets are often introduced even for old houses. This is the case at Carron, Carronshore, and Carronhall, and has made a vast difference in the amenity of the rows.

Fig 16.

The introduction of water closets must usually be conditional on the practicability of purification of the sewage before discharge into a stream. In some cases tidal waters may be the natural point of effluence, and no treatment would be required. This is the case at Fallin. In the special drainage district which embraces the Carron rows the sewage is treated. East Plean, where some houses have water closets and others are in course of being provided, already constitutes a special drainage district, with septic tank and percolation and filter-beds. Independently of the existence of water closets, liquid refuse from village dwelling houses and washing houses is commonly itself discharged under conditions making purification necessary.

Where water closets are provided dry refuse is easily disposed of. By far the best system is its deposit in dust-bins or pails, and daily removal therefrom by cart. This practice is followed with the best results by the owners at Fallin, and by the Sanitary Authority at Carron Company's villages just named, which are within a special scavenging district. It is being arranged for also at East Plean.

Dry Closets.- Privacy and responsibility should always be aimed at in respect of privies as well as water closets. In the large modern village of Cowie, water closets have not yet been introduced owing to present impossibility of getting wayleave for a sewage drain, but it is expected that this will shortly be obtained. I mention Cowie because, even with its dry-closet system, privacy has been reasonably achieved by the closet being placed in an annex near the house door. The photograph (Fig. 17) fails to do justice to it because only one side of the semi-enclosure is included. The plan on page 27 shows the arrangement better. But a water closet is much better than a privy in such a situation.

Fig 17.

The Block System.- In the older, and in some modern collieries privacy and responsibility: are rendered very difficult by the block system of outhouses which is almost universal where dry closets are provided. The situation of these blocks, is shown in the diagram at pages 13 (Fig 1), 29 (Fig 11), and 32 (Fig 14), and is well indicated in the photograph (Fig. 2) opposite p. 14. As a rule the blocks contain wash-houses, coal-houses, privies, and ashpit. It is true that the closets are always on the further side from the dwellings, but there may be other dwellings beyond, and in any case they cannot be approached without a degree of publicity, which is very deterrent to women. In some rows, in despair of keeping doors in order, brickwork screens have been built instead.

Back Doors.- It may be pointed out here that in connection with the disposal of refuse the want of a back door to a house may be a very great inconvenience. In most mining villages the roadways are private, and the blocks of outbuildings are in front of the houses, so that access to them is from the front doors. But occasionally a miners' row faces a public road, and the outbuildings are at the back. If there are no back doors the occupiers have to carry their refuse along the front street, and then through a close or passage to the back. But the row may have no such passage, and buckets of refuse may have to be carried right to the end of the houses, and thence into the back yard. In such cases doors should be opened in the back walls to allow direct access to the premises in the rear.

(2) COAL STORAGE.

The existence of a domestic coal cellar has only a very indirect bearing on health. But it is manifest that every dwelling should have a convenient place for storing fuel. We have seen that in modern rows this is always provided, though the Building Bye-laws cannot compel such provision, but that in many old rows there are no coal houses, and the immemorial practice is to store coals under the kitchen bed. This creates dirt, and prevents the cleaning out of the space under the bed. Absence of coalhouses is a consistent cause of complaint, but when their provision is suggested to the owners it may be replied that they would not be used, and I am bound to admit that some people who have habitually kept coals under beds do not always take readily to the use of coal-houses, but they soon learn. Also, it may be urged that coals are liable to be stolen from an outhouse. But that entirely depends on the kind of outhouse. If conveniently situated and reasonably constructed with a 'good door and lock and key it will certainly be used. If instead there are insecure wooden sparred gates, and if the village is not under proper supervision, jerry-built coal houses may quite well get into disrepair as a result of destructive mischief. An old row of ruinous coal houses may sometimes be seen with the gates entirely gone, and household refuse dumped where the coals were intended to be kept. Very occasionally, where the dwellings are quite close to the mine shaft, the consent of the miners is obtained to an arrangement whereby the colliery firm supplies coals freely to the houses, and makes a deduction from the wages. No coal-cellars are needed under such an arrangement, for which the reasons are obvious.

Go to next page

Go to next page